Why size really does matter

Does it actually matter how many singers and instrumentalists you have when performing music? Nicholas Keyworth has been discovering that size really does matter…

When Handel first performed his Messiah in 1742 at the Fishamble Street Music Hall in Dublin he presented a work for modest vocal and instrumental forces. In many of his performances he is known to have used just 19 singers for both chorus and soloists – and sometimes even less. The orchestra in Dublin comprised of just strings, two trumpets, and timpani.

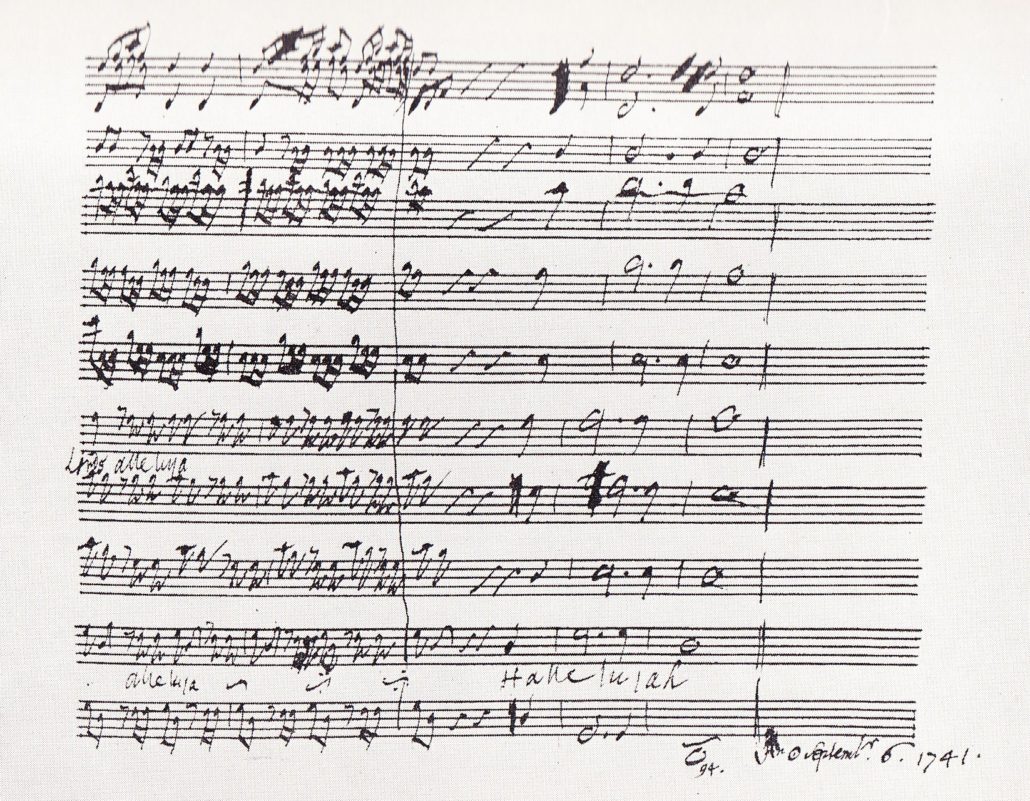

Hallelujah score, 1741

Like most baroque composers, Handel’s instrumentation in the score is often imprecise. Many of the instruments and even the actual music was assumed and did not need to be written down – later copyists would fill in the details.

It was in the years after his death that the work was adapted for performance on an increasingly larger scale, with bigger orchestras and choirs. Whilst in Germany performances remained relatively true to Handel’s original, in Britain and the United States they moved away from Handel’s performance practice becoming increasingly grandiose.

Great Handel Festival

In New York in 1853 for example, it was presented with a chorus of 300 and in Boston in 1865 with more than 600. The Great Handel Festival was held at London’s Crystal Palace in 1857 with a chorus of 2,000 singers and an orchestra of 500.

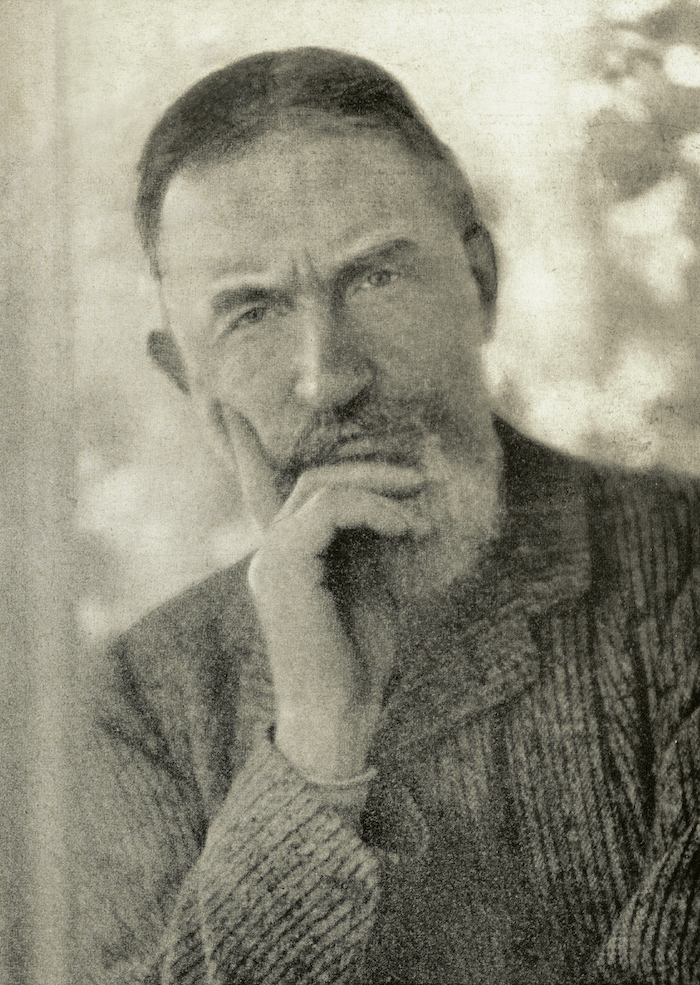

Incredibly, by the 1860s even larger forces were being assembled. Bernard Shaw was so incensed that he wrote:

Bernard Shaw

‘Why, instead of wasting huge sums on the multitudinous dullness of a Handel Festival does not somebody set up a thoroughly rehearsed and exhaustively studied performance of the Messiah with a chorus of twenty capable artists? Most of us would be glad to hear the work seriously performed once before we die.’

In the early 20th century, as the heyday of Victorian choral societies waned Sir Thomas Beecham noted a ‘rapid and violent reaction against monumental performances’ and appealed that ‘Handel should be played and heard as in the days between 1700 and 1750’.

The general trend towards authenticity had begun. This was the beginning of the counter attack which was to continue throughout the century in an attempt to return to something of the scale and sound of the original.

’Is it not time that some of these ‘hangers on’ of Handel’s score were sent about their business?’

– The Musical Times

New edition of the score were needed working from Handel’s original manuscripts rather than from corrupt printed versions with errors accumulated from one edition to another. Although some choral societies today still roll out their annual Messiah these are now appearing decidedly old-fashioned. Today, ‘authenticity’ is more the norm and brings with it a freshness an clarity akin to removing centuries of old varnish from an old master to reveal the vibrant colours and crispness of the detail underneath.

Restoration before and after

This approach will certainly be true of the Oxford Bach Soloists performance of Christmas Baroque on 16 December at St Michael’s Church. And it’s not just Messiah which we will be able to hear with ‘clean ears’, extracts from Bach’s Magnificat and his cantatas, music by Purcell, Praetorius and Corelli with his delightful Christmas Concerto will all be given an authentic ‘restoration’ with small scale focused forces under the expert direction of conductor Tom Hammond-Davies.

Join us for Christmas Baroque

‘Absolutely perfect in every way’

– Oxford Mail

CHRISTMAS BAROQUE

Saturday 16 December 7.30pm

St Michael’s Church, Broad St.

Corelli Christmas Concerto

Handel Messiah (excepts)

Pretorious Es ist ein Ros entsprungen

Bach Magnificat (excepts)

Purcell Behold, I bring you glad tidings

Bach Air on a G string BWV 1068

Bach Wachet auf (excerpts)